The contrast between two countries is immediate. The Thai side had an immaculate highway, road rules and a huge sparkling new temple. The Cambodian side has dust and potholes, cows in the road and a feeling of adventure. We’re cycling on the right for the first time in ages and it feels like trying to write with my left hand.

We stop at the first couple of cash points we find, but our cards don’t work. The third ATM will only dispense notes of US$100. The Cambodian riel is pretty worthless – it can’t be changed outside of the country – and many people prefer US dollars as payment. But in a country where we barely intend to spend $15 a night on a room, a $100 note is just really annoying. I remember banks being an odd source of kindness when we were last here, and sure enough an employee comes out to ask if we need to sit in the air conditioning and tells us that she will exchange the dollars from the cash machine for riel if we’d prefer that. Money sorted, we’re all set for Cambodia.

The paved road from the border lasts for less than 10 kilometres and then it becomes a mess of the deep orange dust that gets everywhere. Some of the road is corrugated, which is hell to cycle on, and the rest of it has so many potholes that it looks like thousands of small meteors have rained down on it. There are so many that’s impossible to weave round them. I’m fairly sure I’ve jarred loose teeth and minor bones, and we’ll find nuts and bolts missing from the bikes when this is over. There’s not much traffic though, but it might be because the road is not suitable for traffic.

This corner of Cambodia has been notorious until recently for animal trafficking and generally being very underdeveloped. It feels very different than the central hub we’d ridden before. It is totally untamed and not far beyond the excuse for a road is rolling wild jungle to the horizon. This area has the second largest untouched rainforest in the region. It’s inaccessible and it looks it.

The terrain is fiercely undulating, with some of the inclines agonisingly steep. It’s almost unbearable in the heat and on the road surface. There is one almighty climb that nearly kills us. The scenery is gorgeous, but we have to wait ages for our ultimate reward, as the top of the climb is lined with tall trees blocking the views, but when it comes we see the Cardamom Mountains blanketed in mist, and the valleys of dense jungle surrounding us.

The villages are very spread out due to the terrain, and lots of people wave and call out as we pass, especially kids. I don’t think many foreigners cycle through here, which makes them all significantly smarter than us. We are covered from head to toe in a coating of red dust at the end of the day, and no matter how much I scrub it doesn’t feel like it’s completely gone.

We’re not interested in beaches, so when we get to a major junction at Sre Ambel, we make for Phnom Penh instead of heading south for the coastal resort town of Sihanoukville. After the junction the surface gets much better and there are even road markings. We’ve left the hills behind now as well, so while it’s not plain sailing because of the intense heat, it’s a much easier ride.

There is severe flooding on the way into Phnom Penh, which makes the last part of the journey gruelling and slow. At the roadside business goes on as normal, with food carts and stalls still operating surrounded by water, so this must be a common occurrence at this time of year. There are cows everywhere wading through the water, and mopeds riding along wherever the water is shallowest, regardless of road direction.

Phnom Penh is an odd city. It is sprawling, dilapidated and chaotic on the outside, with a layer of modern buildings and a core of streets for tourists which are quaint and have that deliberate faux rustic/shabby chic look that people try to achieve with furniture, just applied to entire streets. It is nothing at all like the rest of Cambodia, and neither are the shockingly expensive prices.

We’re visiting the capital to see a couple of sites dedicated to the genocide which occurred in the country under the Khmer Rouge regime. First is a visit to Tuol Sleng, a former school which was turned into a detention, torture and execution centre known as Security Prison 21, or just S-21. It benefits from not being heavily curated, which can unintentionally sanitise a place like this. There are some display cases, and some information panels, but mostly it’s left as-is: Blood-stained floors, exposed barbed wire around the buildings to prevent escape (by normal means on the ground floors, by suicide on the upper ones,) gallows. The money’s been spent on audio commentary headsets, and the narration is incredible and heartbreaking.

The “Killing Fields” site is a way south of Phnomh Penh. When we found out it was a 40 minute tuk tuk ride in the heat costing more than the price of a cheap room nearby, we cycled there instead and took the room. The ride there is very strange. The traffic in the city centre is expectedly insane. Then there are large tracts of land parcelled up for development and some which already has luxury apartments and swanky housing estates (though two of them are called “Chip Mong” and “Shag Gallery.”) There’s a humongous mall of big brand shops, which is open but the car park is completely empty. Everyone ignores the traffic lights at the various mall entrances, since no one is going in or out of them. A security guard blocks a road through a posh housing estate and shoos us away, so we take a long route through some partially flooded villages. The water and mud has seeped onto the road, but it’s just shallow enough for us to get through. This is the poorest area we’ve seen in Cambodia. The streets are mud, there’s rubbish everywhere, the cows are eating the rubbish, the homes are shacks and the kids gawp up at us until waves and smiles break the ice. Round the corner is the entrance to Choeung Ek, which is the best known of the approximately 300 “killing fields” in Cambodia, the result of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge’s social engineering and genocide project.

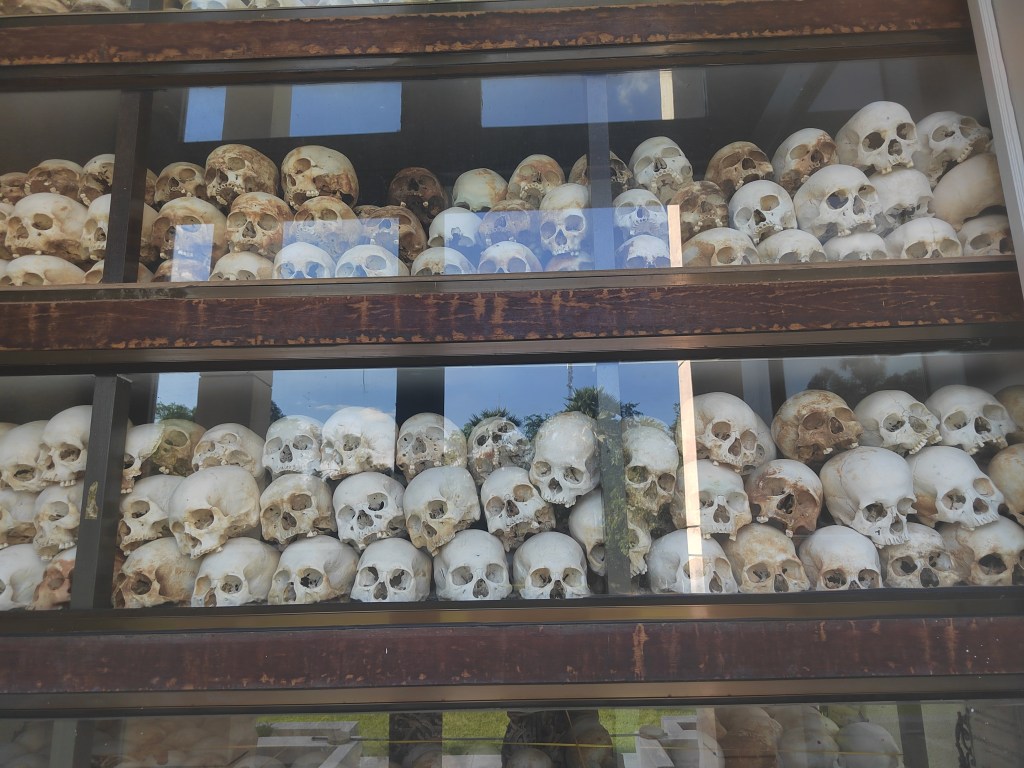

There is very little left here. When the horrors were over, people were angry, desperate and starving. Most of the structures were made of wood, and the remaining population destroyed them and made use of what they could. The sites of the mass graves are marked, as is the Chankiri tree against which the heads of babies sent here were smashed. The Khmer Rouge killed the children of their adult victims, with the sick logic that they might otherwise grow up wanting revenge. The image this place is most famous for though is the Buddhist stupa, an immaculate and serene building from a distance. Inside, towering upwards as far as one can see, are stacks of 5,000 human skulls.

Pol Pot, like many brutal dictators, was a paranoid knobhead who believed Vietnam was planning to invade Cambodia. He pre-emptively attacked Vietnamese border towns, making sure to commit atrocities there too. If the Vietnamese weren’t going to attack Cambodia before, they definitely would now. The Vietnamese army swept to Phnomh Penh, ended the genocide and occupied Cambodia. Pol Pot joined those others who failed to learn a crucial lesson from modern history: Don’t fuck with Vietnam.

We headed south east from the capital towards the coast again, on a safe but busy road that became more scenic the further we went. We are getting tired of the never ending dust and heat, but people here keep buoying us up. It’s hard to find shade, so we usually keep an eye out for shops that have seating, as they let us sit around and have the cold drinks we buy there. It must be very obvious to people how much we’re struggling, as first a woman ushered us to use a cold water tap to cool off before bringing us chairs to sit on. She then gave us packets of food to take with us – sticky rice and dried fish wrapped in banana leaves. Later on another woman gave us some cold bottles of water.

We arrived in Kampot, another town on the tourist trail in this country. It’s supposed to be a “vibey” place in the wanky language of travel sites. It’s very like all other large towns in this part of the world but it has restaurants serving pizza and lots of Europeans to eat it. We are of course part of that crowd adding to the in-authenticity of the places we go, while self righteously proclaiming to ourselves and our blogs that we are travellers, not tourists, and we experience the “real” Cambodia. I think I’m getting travel jaded, or just jaded in general. Richard is feeling the same, that this way of life isn’t as fulfilling as before. The days are full of the miserable heat and dust, and in the evenings we are either in by-the-hour dirty hotels or vibey places like this. It’s getting to the point where the kindness of strangers is barely punching through the depression. We’ve been this fed up once before, and the cure for that was Australia. Maybe a complete change of scenery would do us good again, but that’s a way off given our location. For now we head to the border and go from there.

There’s a dirt road half way to that border, the dust clouds make it impossible to see the road ahead. It’s a good job I cleaned the panniers the night before we left rather than just moping around. We are covered from head to toe again in dust, which becomes a muddy grime as we pour out sweat in the humidity. The many potholes on the road have been filled in by covering the entire surface with dirt and grit. A truck then periodically goes back and forth spraying water to limit the dust cloud. It’s incredibly inefficient.

The second half of the day is on a smaller paved road, and finally it is really nice. Pretty scenery, lots of kids shouting and waving.

The Cambodian border guards seem pissed off that we are there, and I don’t really blame them since we probably appear just as grouchy. The Vietnamese guards are in immaculately pressed uniforms with large Soviet-style military hats. Half of them are stern and steely, ignoring my shit attempts at Vietnamese and our happiness at arriving to a new country. We’re told to unload our bags and put everything through an x-ray machine that nobody is watching. The other half of them are jovial and friendly, which is an odd thing for their kind.

It’s the first new country we’ve crossed into by land for a while. We cannot break our molds of extreme organisation and planning, so we’ve pre-booked a cheap guesthouse fairly near the border in case there were any problems and things took longer than normal. It doesn’t give us much chance to gauge if Vietnam is the answer to our doldrums, but the nature of those doldrums means we both assume it won’t be.

A playlist for the ride:

Leave a comment